You have probably heard of the slogan “Safety First.” On the face of it, there doesn’t seem to be anything wrong with the concept. The premise is that, by putting safety first, you will be keeping yourself and others safe from harm.

But, if you take a closer look at how many companies operate, perhaps even your own, you may find that this slogan may not hold up to scrutiny.

Having a true safety-first mindset implies that safety is the primary reason a company exists. Yet, safety is often not the reason we do things. However, just because safety isn’t strictly first doesn’t mean that safety isn’t a huge factor in our work.

To see that, however, first, one needs to understand businesses.

The Purpose of Business Isn’t Safety

So, what do restaurants, manufacturing facilities, consulting firms, retail stores, and newspaper publishers all have in common? Anyone? Well, for starters, they are all types of businesses.

What does that mean? If a business has a hope of staying afloat, then they are all producing a product or service that they hope to be able to make money from.

When you look at the purpose of businesses, you may find that they aren’t dissimilar to why you may work a job. We need to work to pay for the things we need and, if we are fortunate, at least some of the things we want. If you think about some of the things you need, you probably will start associating some form of cost with them.

Likewise, businesses have costs associated with operations. These will include all costs associated with producing the product or service, such as transportation costs, raw materials, labor, equipment, and energy. While this list does cover many expected costs, it may not cover all operational cost scenarios. After all, businesses can be just as diverse as people.

If we pick, say, a fast-food restaurant, how can you ensure that you will make money from an operations standpoint? Whatever you charge for your dishes and experience must be more than what it costs to provide them. If your service and product are great, you may be able to get away with charging more for them, allowing you to get quality ingredients that may help make the product great.

For a business to achieve its purpose, it takes at least the ability to produce and sell.

These further take other things to make them work. Boiled down, there is a cost to produce and a cost to sell. To make a profit, the product must be sold at a higher price than the cost to produce it.

This is where safety becomes prominent.

The costs to produce and sell something generally assume, for the most part, that processes are working as expected most of the time. But what happens if that isn’t the case? What happens if employees get injured, machines are prematurely damaged, or production slows?

At the end of the day, any loss means a dip in profits if it goes on for too long.

Can Safety Ever Be Number One?

Businesses exist to make a profit, so it probably doesn’t make much sense to say that safety is number one.

Safety is a very important aspect of a successful business, especially in the manufacturing or construction industries. But, if safety isn’t number one, where does it sit in the list of priorities a business may have?

Setting priorities can be tricky, but it is safe to say that safety should be very high. Looking at safety in terms of costs versus income may help put things into perspective on how to tackle things. As discussed previously, for a business to be profitable, it needs to sell its product or service at a higher fee to customers than it costs the business to produce it.

Costs should be easy to identify, but sometimes some costs are overlooked or buried. Do you consider the costs of:

- unexpected equipment failures

- injured employees

- rework costs

- process inefficiencies due to new people?

These unexpected costs add to the overall cost of production. It doesn’t stop at what’s obvious either. It is obvious that if someone burned a food item, then that is so many cents or dollars of wasted raw materials. But there is also wasted labor to produce a product that you can’t sell. And yes, there’s even additional cost for disposal of that waste.

Errors can hit you hard.

Now consider that that same employee seriously burned themselves such that they needed immediate attention. Others in that area would need to respond, taking them away from their normal jobs, and thus either slowing production or grinding it to a halt. The employee may need first aid, medical attention, transportation to medical facilities, and the like. There is also the need of reporting the accident and investigating it. That takes time away from production as well.

All the described activities take labor and some resources away from the business and putting it toward something that generally should not happen — not to mention the fact that a person was burned badly enough to need medical attention!

The costs do not stop there either. Oftentimes with workers compensation, there is a deductible to pay, which means that up to a certain amount, a company is coming out of pocket for that injury. If the employee can come back to work, they may not be able to perform their full duties, lowering overall productivity.

Do you see how one serious injury can snowball? And we didn’t even cover possible legal and regulatory ramifications.

Should Safety Be an Add-On?

We know that not tending to safety can greatly affect operational costs. So, how do you tend to safety properly? Well, if you have a sufficiently old facility or process, without full safety designed in at initial construction and implementation, you have two major choices:

- Replace the equipment with more up-to-date models, complete with applicable safety features and design.

- Upgrade and update the existing equipment.

It is often far less expensive to add safety features to equipment and facilities rather than buy a new piece of equipment. Depending on your industry, it just doesn’t make practical sense to buy a new piece of equipment due to the extremely high upfront cost. This can seem to be the most desirable option because of the lower upfront cost of updating a piece of equipment. But remember, most machines are quite complicated, and modifications aren’t as straightforward as they seem. Older equipment and processes often are less automated and streamlined, and more reliant on the manual labor or action of employees.

When safety is being improved through a more add-on approach, a major deterrent to it working correctly is the strongly competing priorities of production and safety.

For instance, when processes that previously have little in the way of safety are improved through the add-on approach, there literally is more to do. But did your required production numbers get lowered by management? Probably not. This means that however strapped you might have been to produce before are magnified by the addition of safety. Well, this is likely the case in the beginning, at least.

There is a learning curve to doing things safely, correctly, and expeditiously. You will likely find that as you learn the best ways to do things with what you have, that you don’t lose much time in your overall operations. But that doesn’t mean you don’t feel it in the short term. If this is not accounted for, employees often will do what the company emphasizes most. Remember why a company is in business, after all!

To properly add safety to existing processes, there will need to be understanding from upper management on what is needed, and an estimate on the time to get everyone up to speed and back to near normal production levels. All the considerations mentioned before must be accounted for by upper management and allowance made in the short term for a given business unit to learn.

This may mean redirecting some business in the short term so that the company’s needs are still being met.

If this is not done, it will encourage people to take shortcuts when they think no one is paying attention. Employees often want to keep their jobs, and if you pay more attention to production numbers than the overall big picture, your employees are likely to catch on to this. Set your company and its employees up for success with a practical strategy to deal with safety culture and process improvements.

Why Safety by Design Works

The approach of integrating or designing safety into how an organization does business is the likely better long-term solution. When taking this approach, you need to look at the whole process of how an organization operates.

For instance, if you have older equipment that is unsafe by today’s standards, you look at why this is the case prior to deciding. Compliance regulations may have changed, but the process may also be very manual. The historical accident reports may show that 56% of injuries at a given site occur from this machine, and the five-year out-of-pocket costs for the company for those injuries amounted to $1.5 million.

The solution to this issue could be to purchase machines that can do more of the manual portion of the work. The machine itself is $400,000, but it can increase the materials processed by 50%. Additionally, it is built with compliant safety features, such as machine guards and e-stops. So, from strictly an injury cost standpoint, the estimated return on investment or ROI would be 1.33 years. It could be better than this depending on things like if fewer employees are used in this process, and a calculation to factor in the improved production time showed increased applicable monetary value.

Safety by design also improves the productivity of the workers.

For an example scenario, where safety wasn’t designed into the activity, to climb up to service the top of a tank, employees must suit up in a personal fall arrest system for both the ladder (because it is greater than 24 feet up) and at the top of the tank (it has no guard rails). Every time an employee needs to do what they may consider a simple five-minute job, it turns into a 10-minute or longer job because of all the requirements they must check and do. They already feel like they are having a hard time getting things done as it is. So, sometimes they don’t wear the safety gear and do tie off.

A redesign could include stairs to access the top of the tank, as well as fitting guardrails and a proper work platform to the tank. This solution now allows for employees to walk up to do their work without needing any additional safety gear or procedures. They are happier because they have fewer requirements, and the company is happy because they are getting more work out of the employee for the same amount of time. In the short term, this solution is more expensive than what was in place. But, given the potential for serious injury and regulatory fines, the long-term cost-saving will likely outweigh the short-term ones in this scenario.

A bottom-line consideration for the integration of safety is that it is intrinsic to the process. You have safeguards built into machines to minimize or eliminate hazards, use chemicals that are not hazardous where possible, design system processes to eliminate the need for most need to enter potentially dangerous equipment, and other improvements in that way of thinking. Where needed, things like procedural and PPE controls are used, but only after reasonable exhaustion of the other processes.

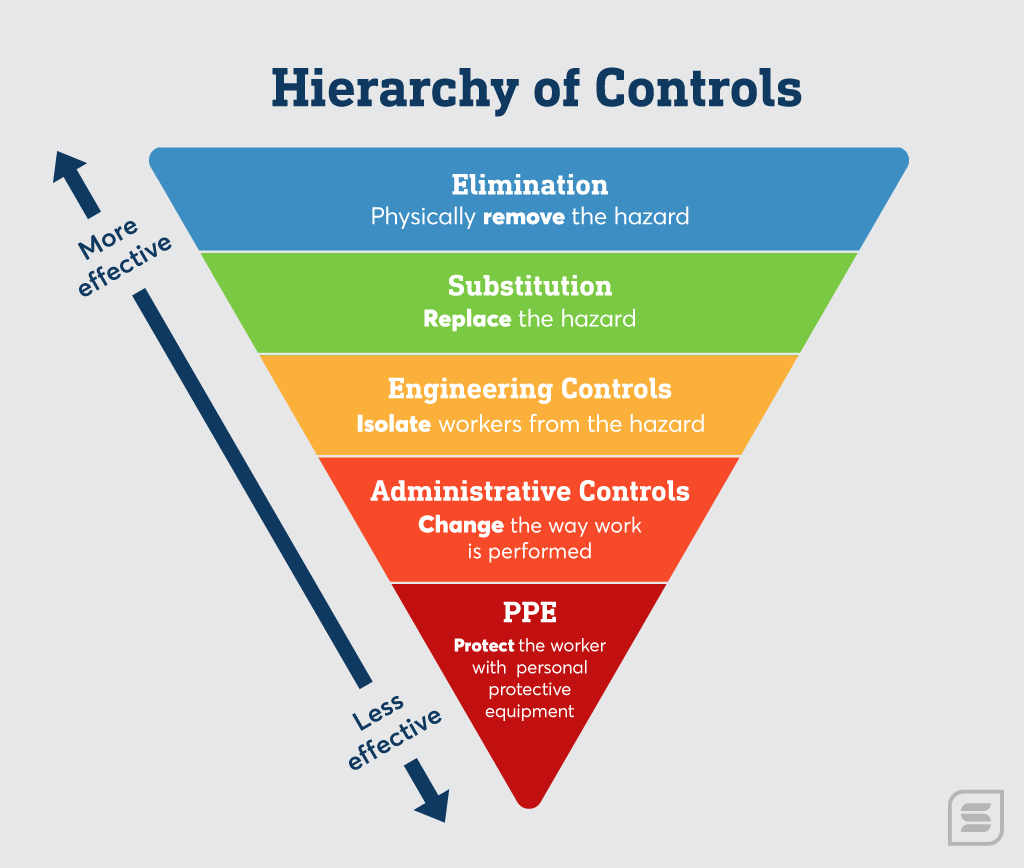

An integrated approach leans heavily on the hierarchy of controls, which generally are as follows and in the given order:

- Elimination or substitution

- Swapping out a hazardous chemical for a less hazardous chemical (substitution)

- Eliminating the need for any such chemical in the process by changing the process.

- Engineering

- Ventilation

- Machine safeguards,

- Automation

- Administration

- Procedures

- Job rotation

- Signage

- Personal Protective Equipment (PPE)

- Hard Hats

- Safety glasses

- Safety shoes

Administrative and PPE controls are generally intended to deal with the remaining risk that is left over after you have used elimination, substitution, and engineering controls.

The risk that remains after all the above steps are used would be your residual risk. Residual risk is just the risk that remains after all controls are put in place. It is unlikely that you can drive your risk to zero, but that doesn’t mean you can’t get close.

If after reviewing your residual risk, a determination is needed to ensure that the risk is at acceptable levels to the company. If it isn’t, a closer look into the hierarchy of controls may be needed. Get ground-level employees involved in this process.

They may know more about the day-to-day considerations of a given process than upper management does. After all, they literally deal with it day after day.